Evaluating Intel QAT for Hash-Based Post-Quantum Signature Schemes

A performance analysis of SHA2/SHA3 offload in LMS, XMSS, and SLH-DSA

Introduction

Intel QuickAssist Technology (QAT) accelerates cryptographic workloads by offloading selected operations to dedicated hardware. This reduces CPU load and improves throughput for applications that rely on TLS, VPN, storage encryption, key exchange, or large-scale hashing.

This post outlines the QAT software stack and evaluates its usefulness for accelerating modern cryptographic implementations.

In this post, I show that QAT hashing is not a good fit for post-quantum signature schemes such as LMS, XMSS, and SLH-DSA: the accelerator only wins for large, contiguous inputs, while these schemes issue many small, sequential hash calls. Instead, QAT remains best suited for bulk TLS/IPsec/storage workloads and asynchronous offload.

QAT software stack

The diagram below shows how applications reach QAT hardware through OpenSSL, the QAT Engine, and Intel’s software libraries:

- Application: Consumes cryptographic services (e.g. TLS termination, IPsec, disk encryption, PKI, secure messaging).

- OpenSSL: Exposes standard crypto APIs; can dispatch operations to software or QAT hardware transparently.

- QAT Engine: OpenSSL engine plugin that offloads supported primitives (RSA, ECDSA, DH, AES-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305, SHA variants) to QAT hardware when available.

- Intel IPP: Highly optimized CPU software primitives (SIMD, microarchitecture-tuned) for symmetric and asymmetric cryptography when hardware offload is not used.

- Multi-Buffer Crypto (IPP-crypto): Batches multiple independent crypto jobs (e.g. parallel RSA, AES-GCM streams) to improve core utilization—useful for high-concurrency servers.

- Intel QAT Driver: Kernel + user-space interface to QAT devices. Two branches exist:

- In-tree (QATlib): Aligned with kernel development model; standardized feature management.

- Out-of-tree: Broader feature set for some legacy or extended hardware. Driver utilities (e.g.

adf_ctl) configure and monitor accelerator instances. Driver families 1.x and 2.x support different hardware generations.

- QAT Hardware: Integrated (selected Xeon SKUs) or discrete PCIe accelerators providing queues for crypto and compression services.

- QATlib: User-space library exposing a stable API to submit crypto jobs to QAT hardware or to fall back on software paths.

Key Points

- Applications typically call OpenSSL, which can use the QAT Engine to offload to hardware or fall back to software (IPP, IPP-crypto).

- QAT Engine is designed specifically for hardware acceleration.

- Intel IPP and Multi-buffer Crypto provide CPU-based optimizations when hardware acceleration is unavailable or unnecessary.

- Multi-buffer Crypto boosts performance by parallelizing cryptographic operations across multiple data buffers, which is ideal for high-concurrency servers.

Cryptographic support

The list of algorithms supported by QAT is documented in the official QAT documentation. Support varies by hardware generation; the driver detects availability. If an algorithm is unsupported, its context initialization returns CPA_STATUS_UNSUPPORTED. Numeric algorithm IDs are defined in the driver sources here.

For this study, the relevant hashing algorithms provided by the installed hardware are:

- SHA2-256

- SHA2-512

- SHA3-256

(SHAKE is not supported on this device.)

Quantitative analysis

We assess whether QAT hash implementations are useful as building blocks inside post-quantum signature schemes - LMS and XMSS.

Measurements compare a conventional optimized C implementation (running on the host CPU) with one-off QAT hash requests submitted via QATlib. Single-shot calls reflect PQ use cases: many small, latency-sensitive invocations rather than bulk streaming. Inputs up to 4 MB stay within QAT request size limits; larger sizes are not relevant for these schemes.

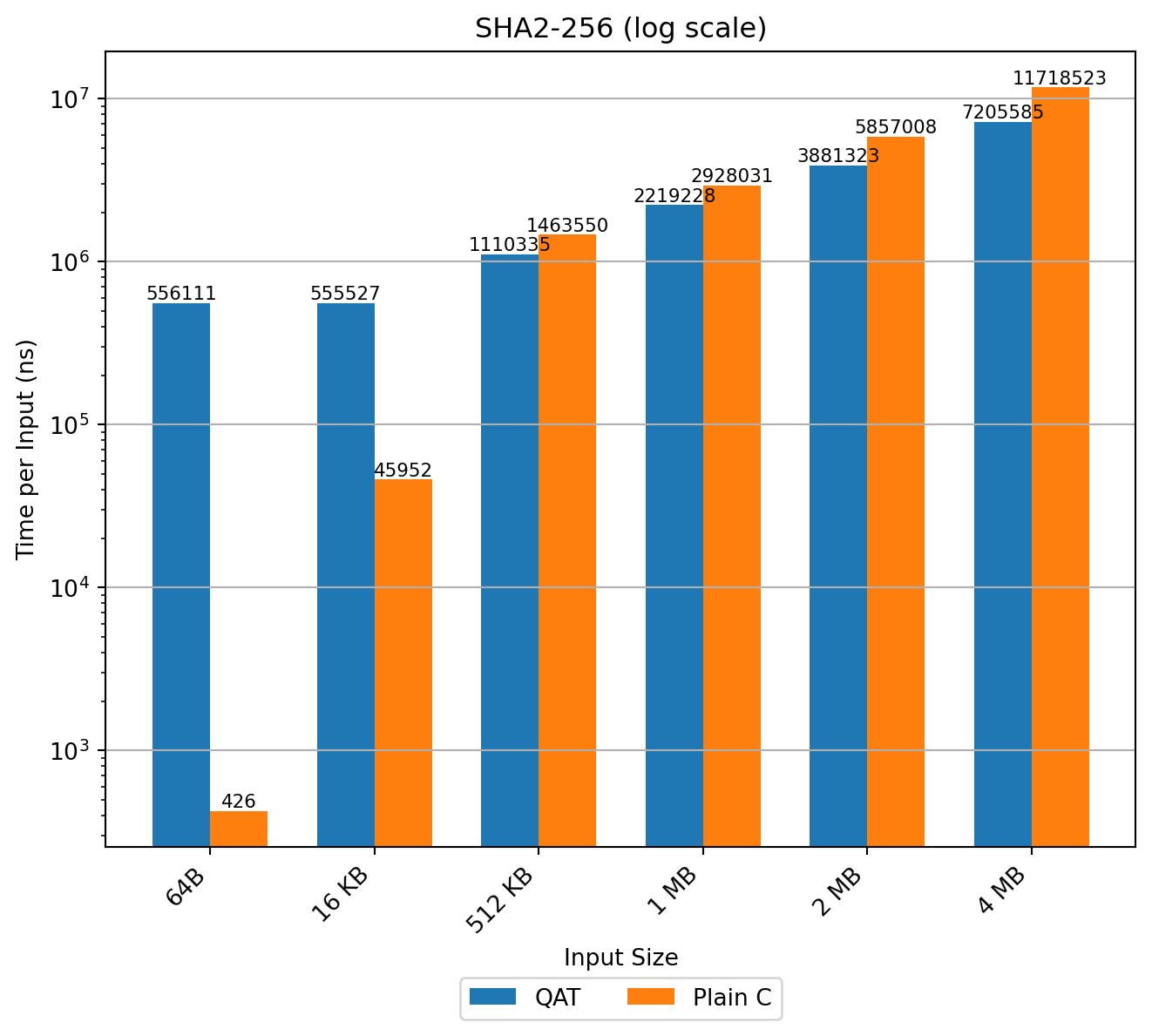

SHA2-256

In LMS (and similarly XMSS) SHA2-256 dominates runtime in key and signature generation. The inner loop for computing K (RFC 8554) iteratively applies the hash to ≈55‑byte inputs; the sequential dependency prevents parallelization:

4. Compute the string K as follows:

for ( i = 0; i < p; i = i + 1 ) {

tmp = x[i]

for ( j = 0; j < 2^w - 1; j = j + 1 ) {

tmp = H(I || u32str(q) || u16str(i) || u8str(j) || tmp)

}

y[i] = tmp

}

K = H(I || u32str(q) || u16str(D_PBLC) || y[0] || ... || y[p-1])Characteristics:

- Strictly sequential inner chain (no batching benefit). The intermediate value

tmpmust be computed sequentially and cannot be parallelized. - Very small message size per hash call (55 bytes per invocation).

Benchmark results (time per input, log scale) show QAT incurs large fixed overhead for small buffers; advantage appears only beyond ≈512 KB. This makes QAT hashing unsuitable inside LMS/XMSS constructions: cumulative latency increases sharply when each tiny hash call pays the fixed offload cost.

Consequently, using QAT-based hash functions as components within LMS, XMSS, or SLH-DSA implementations is not advisable, as it would result in a substantial performance penalty.

Conclusion: explore specialized hardware-assisted chaining (e.g. PQPerform-style offload of the iterative compression loop) rather than generic QAT hashing. Such approaches, however, require hardware features not exposed by QAT.

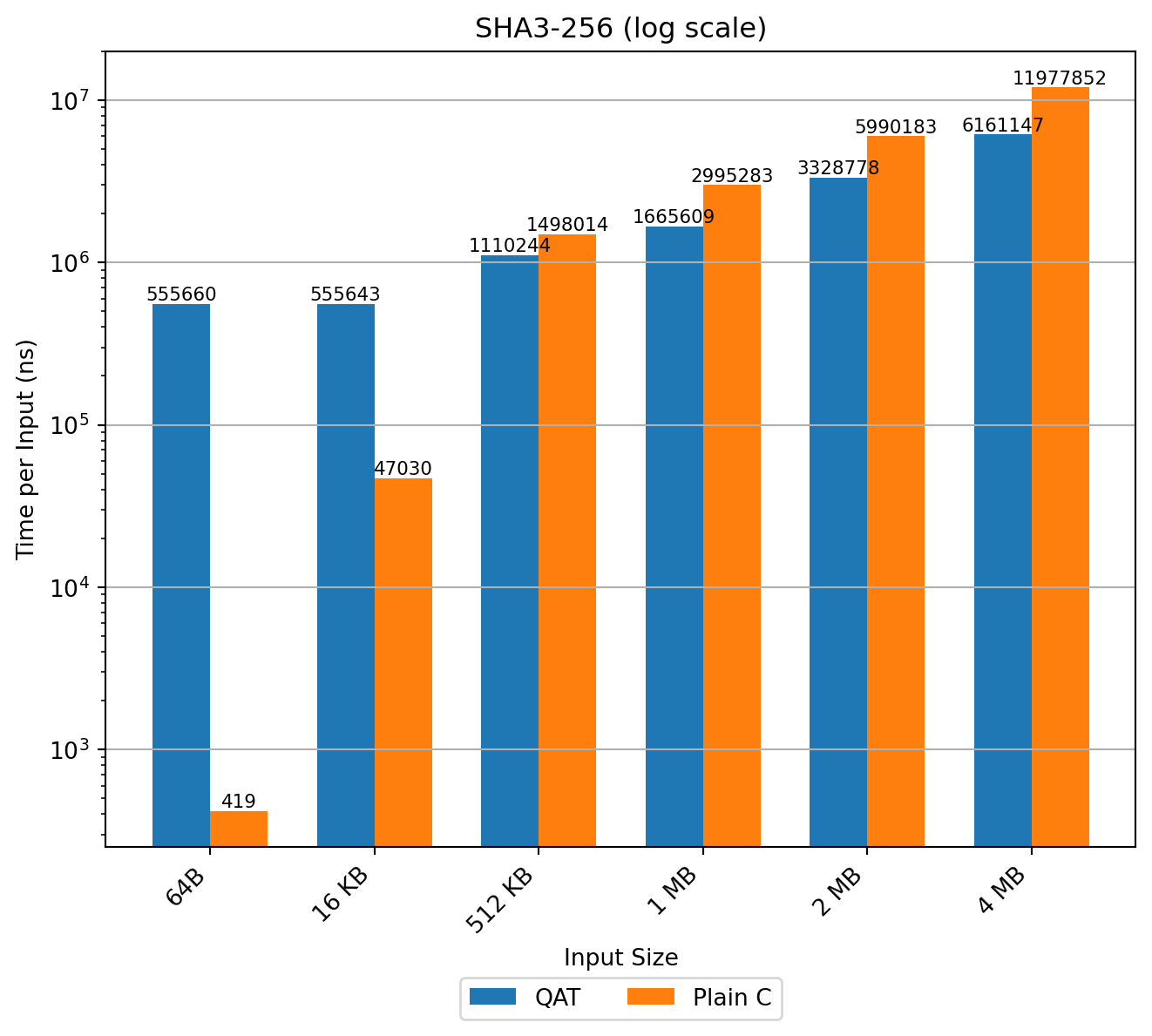

SHA3-256

SHA3-256 offload shows similar scaling; hardware improves absolute times versus SHA2 but still requires large inputs to amortize setup. For PQ schemes with many sub-256‑byte or kilobyte-scale hashes, CPU software remains superior in both latency and energy.

The results are consistent with those observed for SHA2, with SHA3 showing noticeably better hardware performance.

Conclusion: The hardware supports SHA3-256 but not SHAKE. Performance characteristics are similar: QAT only overtakes the CPU at large buffer sizes, making it unsuitable for PQ signature schemes where hashes are small and sequential.

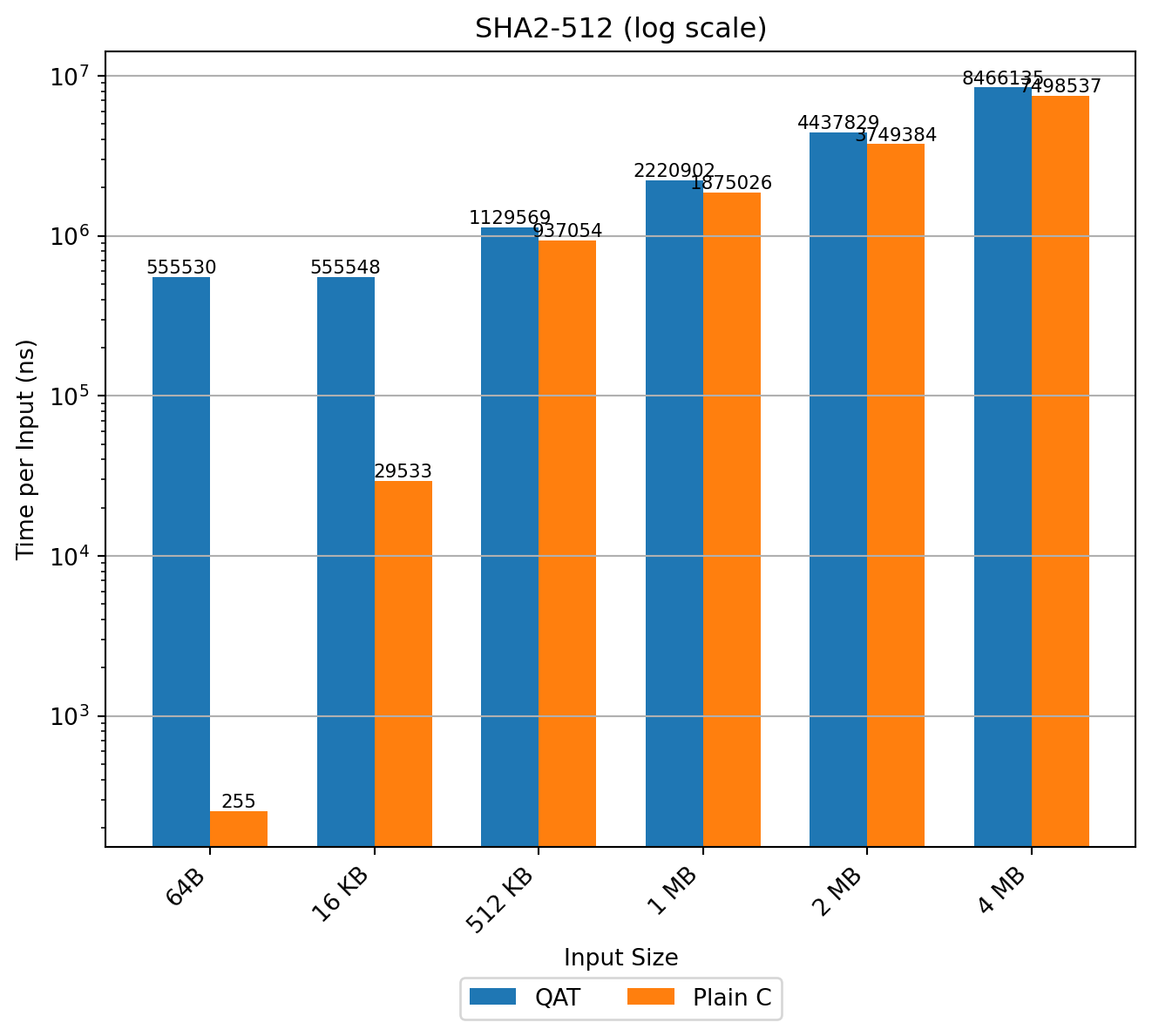

SHA2-512

Used in SLH-DSA. Host software (64‑bit words) outperforms QAT across all tested sizes up to 4 MB. The 64‑bit variant also beats SHA2-256 on the same platform, as expected due to native word operations.

Conclusion: For SHA2-512, QAT never outperforms the host CPU at any tested size. Software remains the optimal choice for SLH-DSA workloads.

Overall findings

- QAT hashing favors large, contiguous payloads (bulk TLS record digestion, storage integrity, deduplication).

- PQ signature schemes issue numerous small, sequential, data-dependent hash calls—poor match for queue-based accelerator semantics.

- Offload overhead dominates for sub‑MB inputs; no throughput crossover in practical PQ parameter ranges.

- Optimized host implementations (vectorized SHA2/SHA3) yield lower latency and better scaling for LMS, XMSS, SLH-DSA.

Conclusion: For post-quantum signature workloads on 64‑bit systems, retain optimized CPU hash functions. QAT hashing is not an effective accelerator for their internal iterative constructions.

Technological Fit for QAT

To realize these benefits, applications must integrate QAT asynchronously. Offloading compute-heavy primitives frees CPU cycles and improves throughput, particularly in high-concurrency environments.

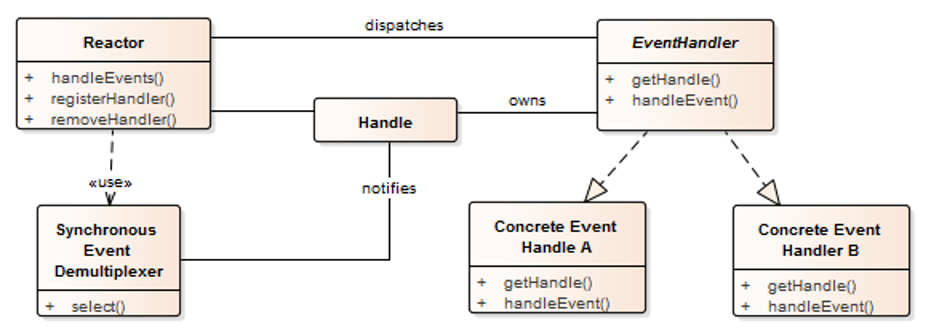

A key enabler is asynchronous execution. In the past, Intel invested in OpenSSL by implementing ASYNC_JOB infrastructure. This functionality is based on reactor pattern, which we describe below.

Asynchronous use of the QAT_engine. The reactor pattern.

The reactor software design pattern is an event handling strategy that can respond to many potential service requests concurrently. Its key function is to demultiplex incoming requests and dispatch them to the correct request handler. By relying on event-based mechanisms rather than blocking I/O or multi-threading, it’s designed to handle numerous concurrent I/O bound requests with minimal delay. Request handlers (here QAT engines) are registered as callbacks with the event handler for flexibility and separation of concerns.

The Reactor pattern excels at managing asynchronous I/O. QAT is accessed asynchronously; requests are submitted, and the application is notified later via polling or a callback. This direct match means a Reactor-based application architecture can effectively handle QAT operations without blocking its main event loop. This is typically used for TLS hardware acceleration: each engine is implemented as a request handler within the reactor. Such a design minimizes connection-establishment latency in environments that handle multiple requests at the same time.

TLS offload

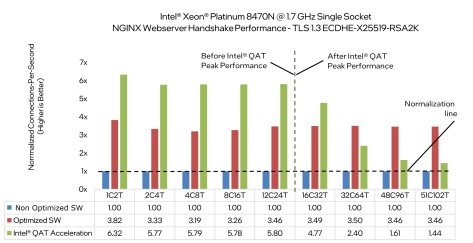

With asynchronous execution available in OpenSSL, Intel performed a measurement study showing performance improvement when offloading TLS. The study goes into great detail on how the measurements were done.

The conclusion that is particularly interesting is that QAT throughput for TLS saturates beyond 16 cores for RSA2K/ECDHE-X25519.

It would be interesting to see a similar measurement study focused on post-quantum (PQ) schemes, namely the following combinations:

Key Exchange: X25519-MLKEM768, Digital Signature: RSA-2048 This reflects the most commonly used hybrid setup in today’s web traffic.

Key Exchange: MLKEM-768, Digital Signature: ML-DSA-65 A compelling mid-term candidate for fully post-quantum TLS session establishment.

Key Exchange: MLKEM-768, Digital Signature: FN-DSA-512 Arguably the most performant post-quantum option for future web communication.

A comparison of QAT, software implementations, and an implementation on a GPU (e.g. cuPQC) could provide a realistic view of performance trade-offs across hybrid and fully post-quantum scenarios.

QAT ecosystem: IPP and Multi-buffer Crypto

This part describes in more detail the software components used in the QAT ecosystem.

Integrated Performance Primitives (IPP)

Intel IPP is a set of software libraries optimized for Intel processors that provides a variety of cryptographic primitives. They are optimized for latency and throughput by using Intel’s ISA crypto extensions (traditional software acceleration, leveraging SIMD, NI, etc.). IPP implements operations like AES, RSA, ECC, hashing (SHA), and compression algorithms.

Multi-buffer Crypto

A specialized library developed by Intel and often packaged alongside IPP, designed specifically for parallelizing cryptographic operations across multiple independent data buffers simultaneously. It optimizes performance in multi-threaded or asynchronous environments by batching multiple independent cryptographic operations and processing them concurrently. Particularly useful for ciphers like AES-GCM, where latency can be hidden by parallelism.

It’s important to understand that they are designed explicitly for parallel workloads. This solution achieves significantly better throughput by processing multiple buffers concurrently, even within a single thread.

Ideal for high-throughput networking (server side) scenarios, VPNs, and SSL/TLS termination points, with multiple client connections.

Relationship between IPP and Multi-buffer Crypto

IPP provides baseline cryptographic primitives optimized for single-buffer, high-performance CPU execution. Multi-buffer Crypto takes IPP primitives a step further, optimizing for parallel operations on multiple independent data streams.

Multi-buffer Crypto delivers much higher throughput in scenarios where latency can be tolerated and multiple independent tasks can run in parallel.

Reuse within a cryptographic software stack

When integrating QAT (or any accelerator) into a cryptographic software stack, three patterns are common:

- Integration into the core crypto stack

- Separate companion component alongside the core stack

- Plugin-based integration for open-source ecosystems

Integration into the core crypto stack

This approach embeds HW‑accelerated implementations directly into the core library, exposing a unified API over both software and HW assisted paths. While convenient at the interface level, it significantly increases design complexity and long‑term maintenance burden. A cleaner separation is to keep the core limited to portable software (including CPU ISA extensions), and avoid coupling to device‑specific accelerators.

The same conclusion applies to accelerator SDKs targeting other devices (e.g., GPUs): keeping them out of the core library preserves clarity and portability.

Separate companion component

This mirrors a split design: a pure‑software core and a distinct HW‑assisted component, each with its own repository, release cadence, and maintenance workflow. The separation is practical because accelerator support targets a narrower footprint, while the core aims for broad platform coverage. A companion component can provide a user‑space dispatch layer that selects between accelerator backends and CPU‑optimized code, and can be extended to support additional devices over time.

Plugin-based integration for open-source ecosystems

Here, accelerator support is delivered as plugins for widely used open‑source cryptographic libraries and frameworks. We recommend building and maintaining such plugins following the separate‑component strategy above: plugins integrate with an existing cryptographic implementation rather than re‑implementing primitives. These plugins must handle low‑latency, incremental input processing and asynchronous completion.

This approach delivers immediate value by integrating with real applications—for example, web servers for TLS offload or VPN stacks for key establishment—without requiring application rewrites.

In practice, I favor a portable software core plus a separate accelerator companion and plugin-style integrations for ecosystems like OpenSSL, rather than baking accelerator logic into the core library.

Conclusions

The quantitative study presented in this post was conducted using QAT hardware connected via PCIe. While the host machine used is relatively powerful, the PCIe communication introduces latency during data transfers.

Intel’s 4th Generation Xeon Scalable processors, released in 2023, represent a significant architectural advancement. These processors feature integrated QAT acceleration engines and support for the CXL 1.1 (Compute Express Link) standard. QAT performance on these CPUs may differ significantly from our current results. Preliminary analysis suggests that CXL offers a more efficient communication model between CPUs and cryptographic accelerators, making it a better fit for such workloads. Even with CXL, unless latency drops substantially, the underlying pattern is likely unchanged: QAT is effective for bulk workloads but not for the many small, sequential hash invocations typical in PQ signature schemes.